Teaching AI to See: A Technical Deep-Dive on Vision Language Models with Will Hardman of Veratai

In this episode of The Cognitive Revolution, Nathan hosts Will Hardman, founder of AI advisory firm Veritai, for a comprehensive technical survey of vision language models (VLMs).

Watch Episode Here

Read Episode Description

In this episode of The Cognitive Revolution, Nathan hosts Will Hardman, founder of AI advisory firm Veritai, for a comprehensive technical survey of vision language models (VLMs). We explore the evolution from early vision transformers to state-of-the-art architectures like InternVL and Llama3V, examining key innovations and architectural decisions. Join us for an in-depth discussion covering multimodality in AI systems, evaluation frameworks, and practical applications with one of the field's leading experts.

Help shape our show by taking our quick listener survey at https://bit.ly/TurpentinePulse

SPONSORS:

Oracle Cloud Infrastructure (OCI): Oracle's next-generation cloud platform delivers blazing-fast AI and ML performance with 50% less for compute and 80% less for outbound networking compared to other cloud providers. OCI powers industry leaders like Vodafone and Thomson Reuters with secure infrastructure and application development capabilities. New U.S. customers can get their cloud bill cut in half by switching to OCI before March 31, 2024 at https://oracle.com/cognitive

80,000 Hours: 80,000 Hours is dedicated to helping you find a fulfilling career that makes a difference. With nearly a decade of research, they offer in-depth material on AI risks, AI policy, and AI safety research. Explore their articles, career reviews, and a podcast featuring experts like Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei. Everything is free, including their Career Guide. Visit https://80000hours.org/cogniti... to start making a meaningful impact today.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00:00) Teaser

(00:00:55) About the Episode

(00:05:45) Introduction

(00:09:16) VLM Use Cases

(00:13:47) Vision Transformers (Part 1)

(00:17:48) Sponsors: Oracle Cloud Infrastructure (OCI)

(00:19:00) Vision Transformers (Part 2)

(00:24:58) OpenAI's CLIP Model

(00:33:44) DeepMind's Flamingo (Part 1)

(00:33:44) Sponsors: 80,000 Hours

(00:35:17) DeepMind's Flamingo (Part 2)

(00:48:29) Instruction Tuning with LAVA

(01:09:25) MMMU Benchmark

(01:14:42) Pre-training with QNVL

(01:32:13) InternVL Model Series

(01:52:33) Cross-Attention vs. Self-Attention

(02:14:33) Hybrid Architectures

(02:31:08) Early vs. Late Fusion

(02:34:50) VQA and DocVQA Benchmarks

(02:40:08) The Blink Benchmark

(03:05:37) Generative Pre-training

(03:15:26) Multimodal Generation

(03:37:00) Frontier Labs & Benchmarks

(03:47:45) Conclusion

(03:53:28) Outro

SOCIAL LINKS:

Website: https://www.cognitiverevolutio...

Twitter (Podcast): https://x.com/cogrev_podcast

Twitter (Nathan): https://x.com/labenz

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/na...

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@Cogni...

Apple: https://podcasts.apple.com/de/...

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/...

Vision Language Models

Preface

- We’re aiming to provide an introduction to multi-modal AI - specifically for Vision-Language Models (VLMs).

- This is a “deep dive” from the perspective of someone with a general interest in AI, but it’s really just an introduction to a deep and complex field of vision-language models

- So, we’ll assume familiarity with the general field of LLMs and deep learning but little in the specific area of multi-modal models.

- We can’t possibly provide a paper-by-paper analysis of the field - which is both deep and accelerating, so we’ll try to cover:

- An overview of the most important architectures and trends in research, illustrated via notable models - models anyone building in this space is likely to encounter.

- We’ll touch on the key datasets and benchmarks

- Then we’ll briefly examine recent attempts at “true” multi-modality (MM production as well as ingestion)

- Finally, we’ll look at how the best-in-class models compare

Motivation

- Many obvious use cases for VLMs - medical assistants, content filtering, media content indexing, managing large product catalogues, damage assessment in cars, etc

- Two further reasons being interested in VLMs: one obvious, one less so.

VLMs allow us to explore modality alignment

- In learning how to construct VLMs, we learn a lot about how to build the true, multi-modal models of the future - integrating further domains like audio, touch, LIDAR, etc

- Think about robotics: the range of sensory inputs that need to be integrated to cook a meal or perform a medical procedure.

MM Understanding may be important for AGI

The arguments for

- The human brain uses cross-modal integrated information to determine which concepts are activated. E.G. the McGurk effect

- The centrality of multi-sensory exploration to concept learning in infants was argued by Piaget.

- In deep learning, there are theoretical results demonstrating that latent embeddings generated from multi-modal data are of higher quality than those from single-modality (see here).

- Some researchers draw inspiration from Grounded Cognition Theory to argue for the importance of multi-modality in AI. (Note that current LMMs do not truly implement grounded cognition as described by the theory.)

The arguments against

- Frontier LLMs already show evidence of high-level abstraction, world models and sophisticated reasoning. There’s no obvious ceiling on performance in view as of today.

Vision Language Models

- If we’re Googling…:

- Large multi-modal model (LMM) and Multi-modal Large Language Model (MM-LMM or MLLM) generally mean the same thing.

- Vision-Language Models (VLMs) generally mean LLMs with image (and often video) understanding capabilities.

- VLMs are where most research has occurred to date. Some recent VLM architectures can natively generate image outputs also.

Vision Transformers

- The two minute overview.

- Introduced in 2020 by a team from Google, the canonical paper is An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale

- Previously, most vision models had been based on CNNs, where stacks of convolutional filters learned to extract successively more global features from images.

- The idea was to see whether the vanilla transformer architecture (without any of the inductive biases of a CNN) could learn to extract the features from an image.

- The recipe is as follows:

- Divide the image into patches (originally of 16x16).

- Apply a (trainable) linearizing embedding to each patch to yield a “token”

- Feed the sequence of patches into a transformer encoder, using full attention

- Like BERT - add a [CLS] token and train the ViT on an image classification objective.

- Key finding: with scale, the transformer architecture beats CNNs.

- Note that input image resolution is fixed by design - 224 x 224 in the original paper

- If this were a LM encoder, normal practise would be to apply a pooling operation over the hidden states to extract an embedding vector

- However, for VLMs, normal practise is to extract the entire sequence of hidden states as this has been found to work better. For a resolution of 224x224 and patch size of 16x16 this would yield 196 visual tokens.

- When we come across a ViT, it’s name will tell us specifics about the architecture, for example, ViT-H/16 is a “Huge” ViT - which translates to 600M parameters, with a patch size of 16.

Aligning images and Text: CLIP from OpenAI (2021)

- Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision

- CLIP stands for Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training

- A canonical model in the field which demonstrates how to align image and text encodings.

- Starting with a vision encoder (e.g. a ViT), a text encoder and a large dataset of (image, caption) pairs scraped from the web…

- jointly train the encoders so that they generate embedding vectors with high cosine similarity between an image and its caption.

- There is a simple linear projection added to each encoder to ensure that they project to an embedding space with conforming dimensions

- This is achieved using a contrastive loss mechanism. Within a batch of N (image, caption) pairs, the loss function penalises similarity between the N^2-N incorrect pairings and dissimilarity between the N correct pairings.

- Once trained, you can use CLIP for image search and other applications.

- It’s not, of course a generative model - but it does illustrate some of the important concepts we’ll cover later on.

The Cross-Attention Architecture: DeepMind’s Flamingo (2022)

- We’ll start with one of the most cited papers in MM research - and a foundational contribution to VLM research.

- The basic pattern, which we’ll see throughout this episode, is that the two modalities are encoded modalities separately - using an image encoder and a text tokenizer

- Then, you design a mechanism to align the two representations so that a LM “backbone” can attend to the visual tokens as it decodes.

- Constructed from a frozen, pre-trained ResNet F6 model (a CNN - not a ViT) and a frozen Chinchilla LM.

- The visual tokens are injected into the frozen LM via learnable, gated cross-attention layers sandwiched between its layers.

- This is cool, because we can freeze the image encoder and the rest of the LM and just train the newly initialised cross-attention layers.

- However, the set-up poses to two challenges:

- Firstly, how can you handle a variable number of images (leading to varying numbers of image tokens) be projected to into a fixed dimensionality?

- How can the large number of visual tokens be reduced, in turn reducing the number of trainable cross-attention parameters?

- Answer: by passing the encoded images are into a Perceiver Resampler (PR) module:

- This module is capable of “selecting” the most critical information out of a long sequence of input tokens without needing to compute a full all-to-all query-key matrix in the attention mechanism.

- This is a achieved by learning a low-dimensional, latent query vector to be used in the module’s attention mechanism, rather than using a projection of the inputs.

- If we have N visual tokens and L learnable queries then this attention mechanism is only O(N x L) and there are only L output tokens. Flamingo sets L = 64

- The PR module can contain >1 layers, with the visual tokens concatenated onto the attention vector each time

- It is effectively resampling the visual tokens, learning what features it needs to query from them during training.

- It’s now easy to see how the cross-attention layers inserted into the LM backbone can learn to effectively query these fixed-size image representations.

- The PR module therefore facilitates an arbitrary number of images (e.g. video frames) to be incorporated into a Flamingo prompt with a consistent and parsimonious image representation.

- To interleave images & text in an input, images are replaced by special tokens, which in turn prompt the decoder to attend to the encoding of the associated image.

- Training data:

- They use the ALIGN dataset, composed of 1.8 billion images paired with alt-texts

- In the ablations, they highlight the importance of interleaved data, collecting the MultiModal MassiveWeb (M3W) dataset.

- extracted from the HTML of approximately 43 million webpages, determining the positions of images relative to the text based on the Document Object Model.

- Sample evaluation tasks included captioning, VQA and OCR

- Works best in a few-shot setting. Very compute-efficient training (once the LM and vision encoder are done) and yet still competitive with task-specific models (as of 2022)

- The basic pattern of using cross-attention layers to integrate the modalities has been used by other teams since.

- What do we learn from this example?

- The cross-attention architecture enables us to freeze a LM backbone and train only the new, cross-attention layers. This is efficient.

- Furthermore, reducing the number of visual tokens using a PR leads to fewer trainable parameters.

- Flamingo team concentrated on architecture and efficient pre-training. For LLMs, it is common to also perform instruction-tuning. How does this work for VLMs?

Instruction Tuning VLMs: Example Model: LLaVA (2023)

- Large Language and Vision Assistant

- Papers for the LLaVA series of models, the original from a mixed Microsoft, academic team

- LLaVA: Visual Instruction Tuning

- LLaVA 1.5: [Improved Baselines with Visual Instruction Tuning](Improved Baselines with Visual Instruction Tuning)

- There’s no LLaVA-NExT paper but the repo is here: https://llava-vl.github.io/blog/2024-01-30-llava-next/

- LLaVA-NeXT-Interleave: Tackling Multi-image, Video, and 3D in Large Multimodal Models

- Video Instruction Tuning With Synthetic Data (a.k.a. LLaVA Video)

- LLaVA-OneVision-72B

- Instruction tuning works well for increasing task competency and diversity for LLMs. Could scaling instruction-tuning serve a similar purpose for LMMs?

- First off, architecture of the original LLaVA:

- Base modules are a CLIP ViT-L/14 (2021 vintage) encoder and a Vicuna 13B decoder.

- Instead of using the cross-attention architecture, the LLaVA team chose a different approach, a simplification of one pioneered by the BLIP series of VLMs from SalesForce:

- Because the vision encoder is taken from a CLIP model, has already been aligned with language embeddings.

- Therefore, it should suffice to train a simple projection matrix align to simply adjust the alignment to work with a different LM - e.g. Vicuna.

- The visual ”tokens” (note - continuous not discrete) are then prepended to the text tokens

- Conceptually, this is similar to prefix-tuning (soft prompting) in LLMs.

- This approach is called the self-attention or auto-regressive VLM architecture.

- Note that this could potentially result in a long sequence of visual tokens since, unlike Flamingo, no resampling takes place.

- The pre-pending recipe lends itself well to a use case where there is a single, static image and a dialogue flow about that image.

- Conversely, it doesn’t support the arbitrary interleaving of images and text in the inputs, nor the use of multiple images.

- N.B. this restriction was been lifted by a later in the series - LLaVA-NExT-Interleave (same recipe, different team - this one from Bytedance)

- This recipe is more parameter efficient than the cross-attention architecture as only the projection matrix is updated during alignment pre-training.

- Key contribution: how to generate high-quality instruction-following data when it is scarce?

- Use the textual content associated with MS COCO images: i.e. the descriptions + labelled bounding boxes

- Use a strong model (GPT4 - not V!) and some careful, few-shot prompting templates to generate:

- a conversation between a questioner and an assistant, framed as though the assistant could see the image.

- What type of vehicle is featured in the image?

- What challenges do these people face?

- a detailed description of the image - using the label & bounding boxes to help GPT4 determine what is going on & generate a richer caption

- complex reasoning questions using the conversation & detailed description as inspiration

- a conversation between a questioner and an assistant, framed as though the assistant could see the image.

- Pre-training

- The CLIP-ViT is frozen, the projection matrix & LM weights are updated.

- Performed on 600K pairs from a captioned images dataset (CC3M) concerted to a “naive” instruction-tuning format of:

- <BOS> GPT4-QUESTION | IMAGE <STOP> Assistant: CAPTION <EOS>

- Fine-tuning

- 158K more complex, multi-turn instruction-following dialogues are used.

- Same free parameters as in pre-training.

- Evaluation:

- Following the Vicuna “LLM as a judge” methodology, GPT4 is used both to generate ground truth answers to novel instructions and as a judge.

- During their evaluations, LLaVA shown to significantly outperform BLIP-2 & OpenFlamingo at complex reasoning tasks and be slightly better at conversational tasks

- Failure modes: little semantic understanding of concepts within the images - e.g. photo of a fridge containing strawberries & yoghurt, answers "yes" to the question "is strawberry yoghurt present"

- So - instruction-tuning works really well and a clever process for synthetically generating the data helps get around the (relative) paucity of high quality multi-model instruction tuning datasets.

- Although the details of creating instruction-tuning datasets are glossed over in the more recent LLaVA series papers, the authors always mention that they are following the “LLaVA recipe”.

- The LLaVA Instruction tuning dataset is available on HF.

- The latest VLM model to follow the LLaVA recipe is the 72B LLaVA OneVision model (LLaVA-OneVision: Easy Visual Task Transfer) (ByteDance) which ranks creditably on the MMMU benchmark.

The LLaVA team observed that most generative VLMs can only respond to a relatively limited range of user instructions. They put this down to a lack of diverse, task-oriented data in the most important datasets (LAION, COCO, etc).

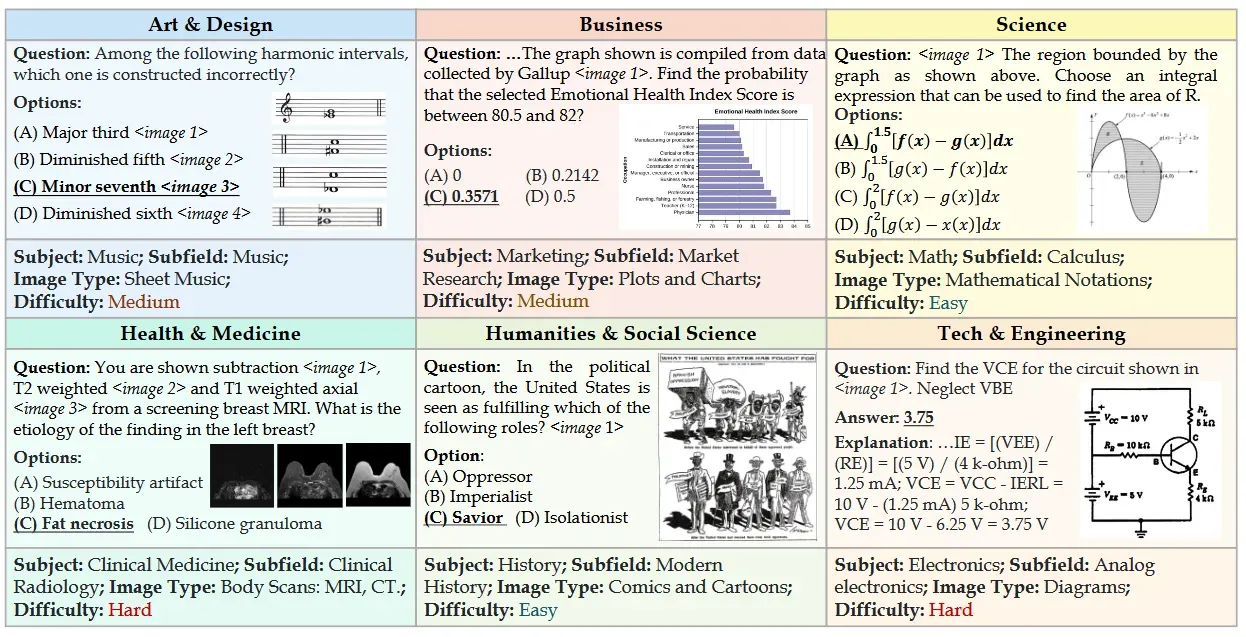

The MMMU Benchmark

- Massive Multi-discipline Multimodal Understanding (https://mmmu-benchmark.github.io/)

- Probably the most well-known and widely reported MM benchmark for VLMs

- Designed to measure three skills: perception, knowledge, and reasoning

- The questions were manually collected by a team of college students from various disciplines and subjects, drawing from online sources, textbooks, and lecture materials.

- Designed to require expert-level understanding from the domain in question in order to correctly answer the questions.

- 11.5K questions ranging over 30 subjects (e.g. history, clinical medicine, electronics, market research, music)

- Many problems will require expert-level reasoning to solve. e.g. knowing how to apply a Fourier transform to solve a problem.

- 95% of the questions are multiple choice (4 options).

- When first released in Nov 23, GPT4-V (top frontier model) scored 55.7% and LLaVA-1.5 (top O/S model) scored only 34%

- Now, o1 stands atop the leaderboard with a whopping score of 78.1% - 8% clear of InternVL-2.5, the runner up.

- Interestingly, GPT4 (text only) using the questions + captions extracted by OCR or LLaVA-1.5, scores 34% on the benchmark - highlighting the important role that reasoning plays in answering the questions

- Error analysis of GPT4V: Roughly evenly split between perceptual errors, reasoning errors and lack of knowledge.

- The Pro version of the benchmark involved removing questions which LLMs could answer, increasing the candidate answers from 4 to 10 and adding a “vision only” input mode

Multi-stage pre-training: the QWEN-VL series from Alibaba (2023/24)

- Qwen-VL: A Versatile Vision-Language Model for Understanding, Localization, Text Reading, and Beyond

- Qwen2-VL: Enhancing Vision-Language Model's Perception of the World at Any Resolution

- The QWEN series follows the self-attention architecture, using Qwen’s LMs as a backbone and a ViT vision encoder.

- A single, cross-attention layer (with learnable queries, similar to the PR) is used to resample the visual tokens, which are then injected, AR-fashion, into the decoder. This resolves the problem with AR architectures of large visual token-counts. Comparison with Flamingo’s PR:

- QWEN-VL uses 256 visual tokens, compared to Flamingo’s 64

- The single cross-attention layer means fewer trainable parameters in the QWEN-VL adaptor (80M) vs 200M in Flamingo - despite the 4x increase in token count

- 2D positional information is added to the visual tokens in QWEN-VL; Flamingo flattened the visual tokens

Training QWEN-VL

- The innovation here is to run a 3-stage training pipeline, adding an extra pre-training stage.

- Pre-training

- 1.4Bn (image, text) pairs from LAION, LAION-COCO, DataComp and Coyo, “filtered and cleaned”

- ViT and cross-attention layers are trained. LM is frozen.

- Images are resized to 224 x 224

- Multi-task pre-training

- To preserve LM performance, some of the pre-training data used for QWEN LM was mixed in.

- Added VQA datasets (GQA, VGQA, DocVQA)

- For grounding tasks, constructed a dataset from GRIT, RefCOCO and others, standardising the bounding boxes and references

- Added synthetic OCR data

- Images now sized at 448 x 448

- LM is unfrozen.

- We’ll see this theme again later on: to squeeze more juice from scarcer MM training data, pre-training on successively more complex tasks with introducing progressively richer input examples works really well.

- SFT

- A 350K instruction-tuning dataset is constructed via a combination of self-instruction and manual augmentation. (Details for the self-instruct process are not given)

QWEN2-VL

- The latest iteration of the QWEN series, QWEN2-72B, sits behind the leading models from OpenAI, Anthropic and Google on MMMU but above all others. The smaller models are open sourced but the 72B class is available via an API. The paper promises that the model will be O/S soon, but nothing yet…

Efficiently scaling VLMs: InternVL series from OpenGVLab (April 2024 onwards)

- Team is from the Shanghai AI Laboratory

- One of the challenges facing (particularly O/S researchers) building VLMs is the training cost.

- Even when using pre-trained ViTs and LMs, modality alignment pre-training is expensive - and, of course, grows with the parameter count.

InternVL

- InternVL: Scaling up Vision Foundation Models and Aligning for Generic Visual-Linguistic Tasks

- Observation: Vision transformers are small and pre-trained separately from the LMs they will eventually be connected to in a VLM. Can we do better?

- They start with a 6B ViT architecture (for reference, a ViT-H/16 class would have around 600M and ViT-G/16 would have 1.8B)

- Training:

- Contrastive pre-training using the CLIP objective on 5B (image, text) pairs, using a frozen LLaMA-7B to embed the texts

- Initialise learnable queries and a cross-attention module to the LLaMA model and conduct vision-language generative training. ViT and LM params are kept frozen, the (image, text) dataset is further filtered for quality to 1Bn pairs and the BLIP-2 loss function is used: 3 components: image-text contrastive (ITC) loss, image-text matching (ITM) loss, and image-grounded text generation (ITG) loss.

- What we have now is a high quality, well-aligned ViT. The team demonstrate that SFT can be performed using a totally different LM, using the auto-regressive approach, and it works really well.

InternVL 1.5

- How Far Are We to GPT-4V? Closing the Gap to Commercial Multimodal Models with Open-Source Suites

- This was the question asked by the InternVM team: why do O/S VLMs lag frontier models? Their answer:

- Scale (obviously)

- Image resolution. Training using 224x224 or 448x448 resolutions means that details are lost, or that documents with a very different aspect ratio are horribly stretched or clipped

- They focused on improving the image encoder:

- They train a new 6B param ViT with a resolution of 448x448 pixels and adopt a “dynamic high-resolution strategy” that segments images into 448×448 tiles, with the number of tiles based on the aspect ratio and resolution of the images. (The tiling configuration is matched to the aspect ratio of the document.)

- a “thumbnail” of the entire original image is concatenated, providing a global view of the content

- a pixel shuffle strategy used to reduce the number of visual tokens by 3/4

- A similar strategy has been employed in QWEN2-VL, which no doubt contributes to its impressive benchmark performance

- Unfreezing the ViT parameters during VLM pre-training to enhances its visual representation capabilities, at the expense of higher training costs.

- They train a new 6B param ViT with a resolution of 448x448 pixels and adopt a “dynamic high-resolution strategy” that segments images into 448×448 tiles, with the number of tiles based on the aspect ratio and resolution of the images. (The tiling configuration is matched to the aspect ratio of the document.)

- Architectually, this is an auto-regressive architecture with a simple MLP to project the visual tokens to the LM.

- Results: competitive with the four, leading VLMs (Grok-1.5V, GPT-4V, Claude-3 Opus, Gemini Pro 1.5) on key eval benchmarks, including: MMMU, OCRBench (SoTA), DocVQA (documents)

InternVL 2 and 2.5

- The team introduce a trick for scaling up their VLMs to use larger LM backbones - up to a QWEN-VL 72B LM . Using a “progressive scaling strategy”, they align the ViT to a smaller backbone, then swap to progressively larger backbones. The claim is that vs. QWEN2-VL’s 1.4T tokens, they use only 120B

- InternVL2.5-78B is currently the top O/S model on the MMMU leaderboard, sitting only behind o1.

- Beats GPT-4o (0513), Claude 3.5 Sonnet (original), Gemini 1.5 Pro on MMMU, TextVQA and OCRBench

LLaMA3-V: large scale SoTA VLM using the cross-attention approach

- Just to prove that the cross-attention vs. self-attention debate is very much unsettled, the LLaMA3-V models have opted for the cross-attention approach.

- Uses the approach of a pre trained vision encoder - a ViT-H/14 - and cross-attention layers, trained on image/text pairs

- They note: As also demonstrated by prior work such as ViP-Llava (Cai et al., 2024), we observe that image encoders trained via a contrastive text alignment objective are unable to preserve fine-grained localization information.

- Recall that one of the reasons that the self-attention architecture seems to work is that, by using a CLIP or InternViT model which has been contrastively aligned with an LM, it’s a small step to re-map the embedded image tokens to another LM - hence a simple MLP connector will suffice.

- They introduce “temporal aggregator” layers and additional video cross-attention layers that operate on a large collection of video-text pairs to learn the model to recognize and process temporal information from videos.

- A fair amount of effort was spent on cleaning, safety-filtering, desensitising, deduplicating and quality-filtering on the MM dataset.

- Machine-generated OCR data is added to the pre-training mix

- They also do some synthetic augmentation of the pre-training images, at scale:

- visual grounding: adding annotated bounding boxes to the images to denote nouns and repeating the annotation symbols in the text around the relevant noun.

- Synthetic captions

- synthetically generated structured images - e.g. tables, latex

- the videos are likewise filtered for quality

- They insert 8 gated attention layers in between blocks of the ViT designed to learn “alignment specific features” prior to training the x-attn layers.

- Unlike other works, they DO NOT freeze the image encoder weights

- Existing LLaMA parameters were not touched during any stage of training, which helped preserve text-only performance.

- Cross-attention layers use Generalised Query Attention (GQA) for efficiency

- For video, temporal aggregation is done on every 32 frames (this is another perceiver-resampler, of course)

- SFT and reward-learning are both performed - the latter with a carefully managed DPO process

- LLaMA3.2 90B is currently the second-placed O/S model on MMMU.

Datasets

- Early VLMs were pre-trained using a large number of image/caption pairs crawled from the web. A popular choice has been LAION, with 5B pairs but newer datasets like DataComp (with 12B pairs) are larger.

LAION

- 5.85 Bn images with text captions extracted from the common crawl.

- Filtered using CLIP to ensure caption-image relevancy.

- The largest MM dataset that is publicly available.

COYO

- 750M image-text pairs, crawled from the web

- Higher CLIP quality threshold was applied than for LAION

- Added some further filtering criteria - an aesthetic score, probability of a watermark, etc

Interleaved Datasets

- Another strategy is to look beyond image/caption pairs and train on a large corpus of web documents. The idea is to download webpages, clean them to retain only the core content and then present it to the LMM - images and texts kept in the same order. This approach has been used by some recent and leading LMMs including MM1 and BLIP3.

- Recent research teams from Apple (MM1), Huggingface (IDEFICS) and SalesForce (BLIP) highlight the importance of interleaved image/text documents in the training mix.

- As we saw, during PT it’s normal to use the next-token prediction objective but simply to mask out the interleaved image tokens and compute the loss over the text tokens only

MINT-1T (2024)

- Multi-contributor team led by SalesForce

- A 1T token dataset including HTML, PDFs and arXiv papers.

OmniCorpus (2024)

- From the OpenGVLab (of InternVL fame)

- 2.2B documents sourced from Common Crawl dumps

- Contains 8B images and nearly 1.6T text tokens

Cross-Attention vs. Self-Attention

- Of the models we’ve discussed so far, only Flamingo and LLaMA3-V have used the cross-attention architecture whilst the rest are based on the auto-regressive architecture.

- On the whole, more teams have chosen to use use the auto-regressive approach.

Parameter efficiency

- The introduction of cross-attention blocks adds (according to Laurençon et al) roughly 25% to an LLM’s parameter count which need to be trained.

- The only new parameters required come from the projection component - which can be as as a linear projection (e.g. the original LLaVA), or a more sophisticated MLP. For self-attention, the count is more like 10%

Training efficiency

- In a cross-attention architecture, the LM “looks up” the information it needs from the embedded visual tokens.

- In the auto-regressive architecture, we have to unroll the visual tokens into the LM’s context window and apply attention across the entire sequence, resulting in lower training throughput.

Dynamic resolution and variable image tokens

- It’s easy to mix arbitrary numbers of visual tokens into self-attention models, because they are treated just like text tokens.

- In cross-attention models, we need to handle this with learnable queries which potentially compresses or shuffles around local features, affecting tasks like OCR or VQA.

The IDEFICS series from HuggingFace

- Laurençon, H., L. Tronchon, M. Cord, and V. Sanh (2024). [What matters when building vision-language models?](arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.02246) (IDEFICS 1)

- Image-aware Decoder Enhanced à la Flamingo with Interleaved Cross-attentionS**

- **Building and better understanding vision-language models: insights and future directions (IDEFICS 2)**

- The authors experimented with both architectures and evaluated the resulting models on a combination of VQA, OCR and captioning benchmarks.

- Key findings:

- When the LM backbones are frozen and only the newly initialised parameters are trained, the cross-attention architecture significantly outperforms the AR architecture. Perhaps not surprising, since there are more free parameters in the former.

- However, when allowing the LM backbone to be updated (using LoRA), the AR architecture performs much better.

- That said, training the LM without LoRA led to training instabilities.

- Improving either the LM or ViT backbone leads to a better VLM. The authors note that comparatively more attention has been focused on the former, rather than the latter.

- Adding a Perceiver-Resample to reduce the number of visual tokens both sped up training (for obvious reasons) but also improved performance.

- This result is at odds with findings by other researchers (e.g. Apple’s MM1 team) who report that more visual tokens and a higher resolution leads to better models.

- Cropping images into “tiles” (rather than processing them in natively higher resolution) seems to work very well as a simple strategy for processing image details. Adding this pre-processing step to the training data boosts performance on document QA and OCR tasks.

- For a fixed number of parameters, increasing the size of the LM backbone has a higher impact on the performance of the final VLM than the size of the vision backbone.

- The use of interleaved image/text documents (e.g. webpages with inline images) seems to be particularly important for few-shot learning.

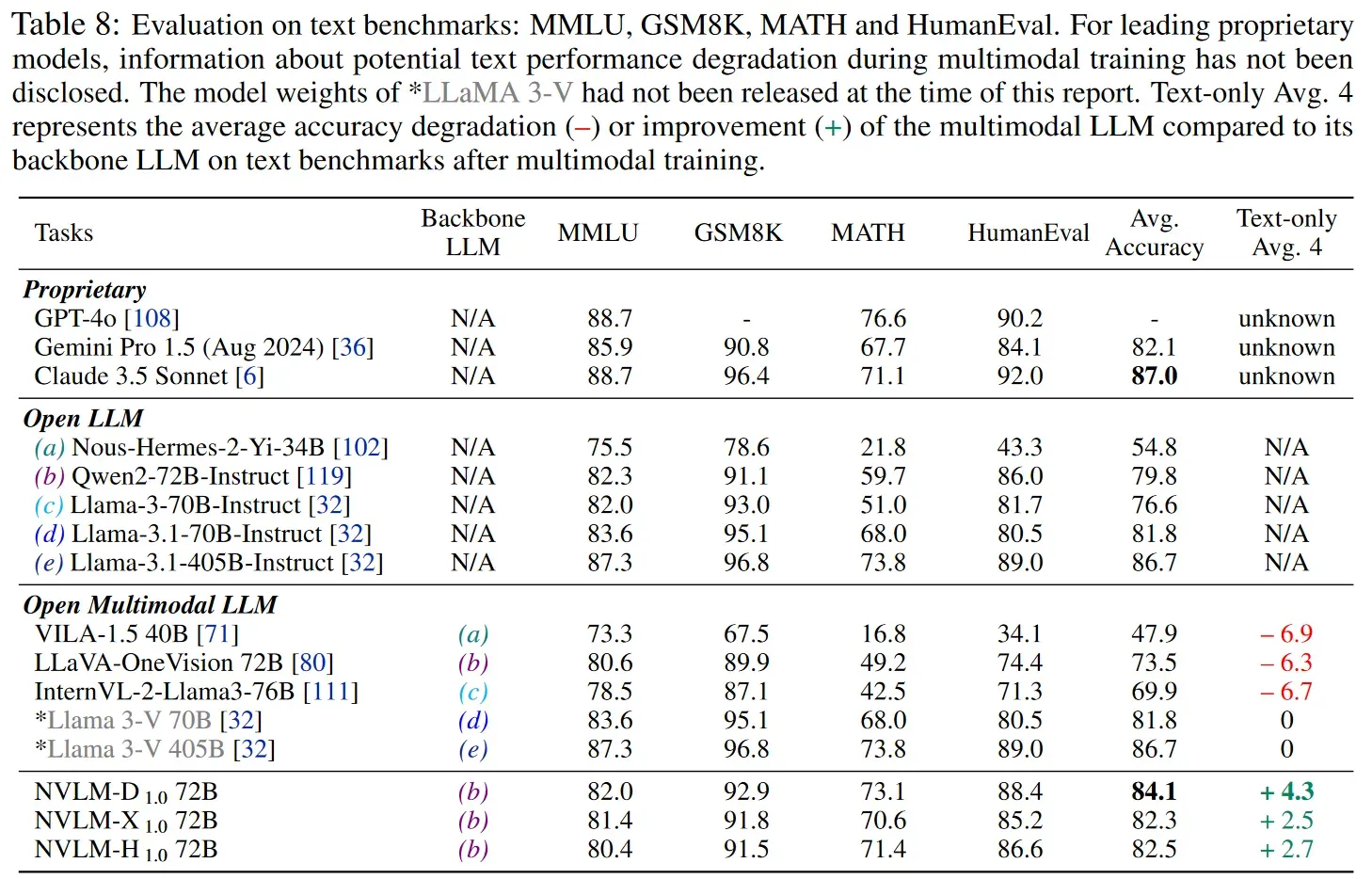

Comparing Architectures: NVLM (NVidia)

- Paper is: NVLM: Open Frontier-Class Multimodal LLMs (https://arxiv.org/pdf/2409.11402)

- They train 3 architectures, using a common LM backbone (Qwen2-72B-Instruct), Vision Encoder (InternViT-6B-448px-V1-5) and training mixture. These are:

- “D” - the decoder-only version

- “X” - the x-attn version

- “H” - the hybrid version

- Comparing X and D, they discovered that D has the best MMU, reasoning & OCR performance whilst X was more efficient to train

- They report that the Perceiver-Resampler seems to affect OCR performance in the cross-attention architecture - probably because it is shuffling spatial information which hurts fine-grained understanding tasks.

- Therefore, they propose “H” - a hybrid model where the image thumbnail tokens are mixed in to the decoder stream whilst the high-res patches are introduced via cross-attention

- This removed the need to unroll all of the high rest image tokens in the decoder, but still gives the self-attention mechanism direct access to the image.

- This sounds like a performance/quality trade-off - and indeed D beaths H on OCR tasks, chart understanding but H actually slightly beats X and D on the MMMU validation set, so I expect to see this hybrid model explored further in the future.

- They curated a high-quality, multi-source, text-only dataset and integrated it into the multimodal SFT stage. This preserved text-only performance - something which often degrades in VLMs.

- To this, they added a MM SFT dataset also comprised of a large number of benchmark and task-specific datasets.

- Interestingly, they saw improvements on LM performance on text-only math and coding benchmarks after multimodal training. They explained this by:

- the superb quality of the curated text-only data

- the significant amount of multimodal math data (e.g., geometry) incorporated into MM SFT blend, which improved NVLM’s reasoning capabilities, regardless of modality.

- Key finding from the NVLM paper: “dataset quality and task diversity are more important than scale, even during the pretraining phase, across all architectures”.

- This is echoed by the HuggingFace team, who spent extensive time curating new, diverse training datasets.

- However, “Models which use techniques to process images at high resolution significantly boost performance on OCR-related tasks but sometimes show reduced accuracy on reasoning-related tasks compared to their low-resolution counterparts.”

- NVLM is currently the third-placed open source model on the MMMU leaderboard, beaten only by the latest InterNVL2.5 model LLaMA3-V

Note the absence of a drop from LLaMA3-V due to it’s cross-attention architecture

Task-specific datasets

- Given the sophistication of interactions we’re looking for in our VLMs, we’d like even larger and more sophisticated task-specific datasets. Hence the work on synthetic data augmentation and complex task generation.

MS COCO (Common Objects in Context) (2014)

- COCO (Common Objects in Context)

- 200K images containing 1.5M objects from 80 categories

- Small, but high quality and important

- Contains High-quality annotations: Each image has detailed annotations including segmentation masks, bounding boxes and captions.

GrIT (2023)

- Not to be confused with GRIT - from AllenAI

- Constructed by a Microsoft research team as part of their Kosmos 2 grounded VLM

- 91M examples extracted from LAION and COCO

- use a pre-trained detector to extract noun chunks and associate them to image regions

- then, expand noun chunks to referring expressions

- noun phrases are explicitly associated with the bounding boxes, resulting in a high quality, grounding dataset

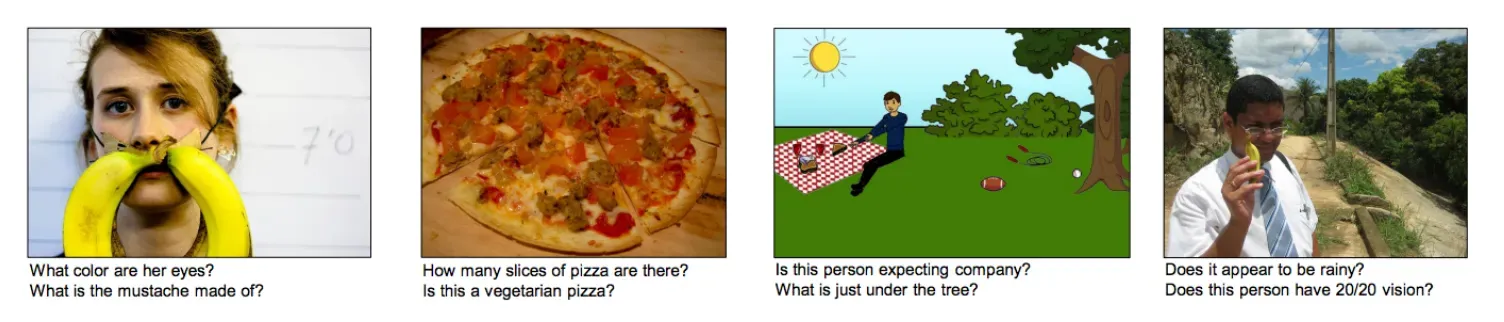

VQA

- Multiple questions per image, multiple answer options per image. Makes for 1M questions in the dataset overall!250K COCO images paired with open-ended questions about images - generated by MTurk workers. These questions require an understanding of vision, language and commonsense knowledge to answer.

DocVQA

- A set of 50K questions over 12K images extracted from a dataset of Industry documents.

- Contains PDF scans, charts and graphs, tables of data, invoices, hand-written notes and business info-graphics

- Task is to isolate and report precise spans of text to match a question: e.g. “What is the invoice number?”

The Cauldron

- 50 VLM fine-tuning datasets bundled up together. Probably the easiest way to acquire FT data now

- Mention this as a great way to find candidate augmentations and prompt structures

BLINK (Academic & AllenAI team, Jul 2024)

- Leaderboard here

- Paper here

- BLINK contains 3,807 multiple-choice questions ranging over 14 common perceptual tasks that humans can solve “in a blink” but which are difficult for VLMs.

- Human performance across the dataset is 95.7%

- Random guessing on BLINK would yield a score of 38.09%

- The authors contend that MMMU questions often reduce to a “dense captioning” task.

- What they mean is, if one replaces the image with a rich caption of the content, MMMU performance does not drop dramatically for a given VLM.

- The interpretation is that most of what MMMU is testing is reasoning and that less emphasis is placed on classic visual perception capabilities.

- Put another way, VLMs are great at learning generalised, compositional features from images which can be associated with language fragments but they lack many of the perceptual primitives that form the building blocks of human visual perception.

- Looking across the 14 categories on the leaderboard, there is a significant range between the best performing model within each category.

Best-solved BLINK tasks

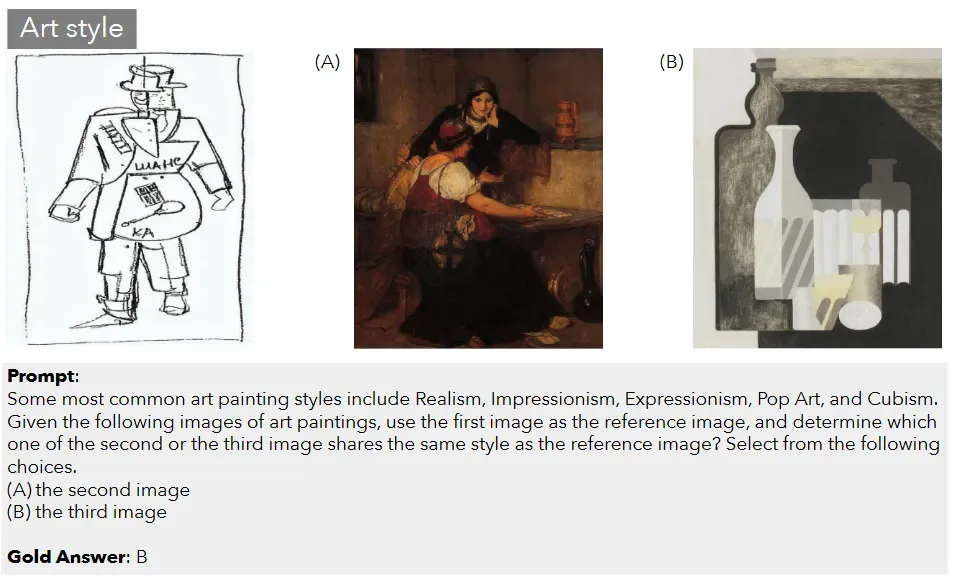

- Art (GPT-4o: 82.91%; Human: 95.30%; Random: 50%). Given one reference painting image and two other paintings as options, the model is tasked with identifying the one that most closely shares the art style of the reference painting.

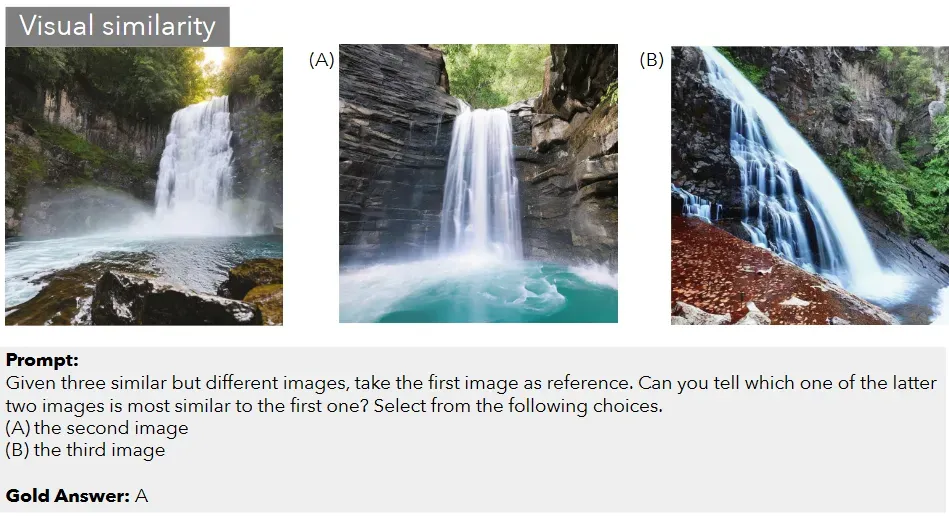

- Visual Similarity. (GPT4-Turbo: 80.74%; Human: 96.70%; Random: 50%). Given a reference image alongside two alternative images, the objective is to identify the image that most closely resembles the reference image in terms of visual similarity

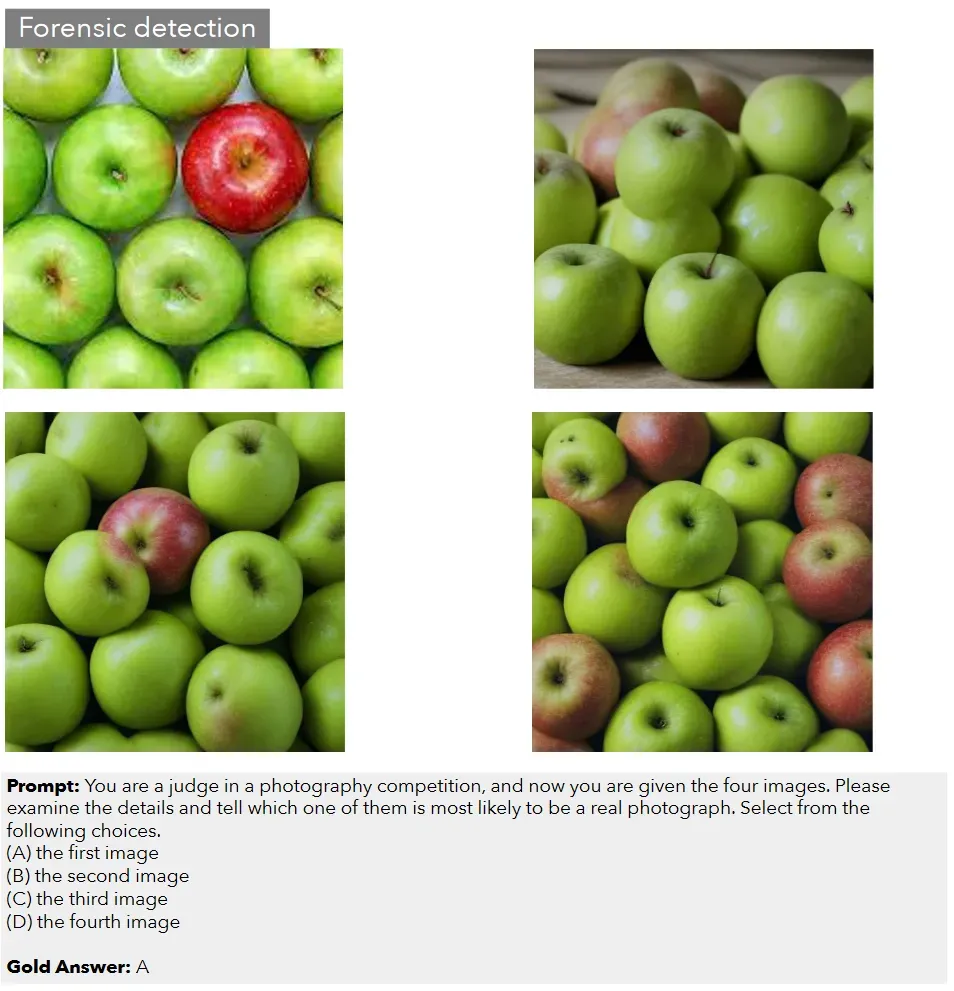

- Forensic (GPT4o: 79.55%; Human: 100%; Random: 25%). Presented with a set of real and images generated by SDXL, the model must select the real one.

Worst-solved BLINK tasks

- IQ Test. (GPT4-Turbo: 32.67%; Human: 80%; Random: 25%) Given visual examples and a selection of images, the objective is to identify the image that either continues the pattern established by the examples or is spatially consistent with them

- Relative reflectance. (LLaVA-1.5: 39.55%; Human: 95.14%; Random: 33.33%). Compare the reflectance (albedo) of two pixels within an image.

- Functional Correspondance (GPT4o - 40.77%; Human: 80.77%; Random: 25%). The task presents an action alongside two object images. One image includes a reference point, while the other offers four potential points. The objective is to select the point that best matches the reference in terms of functional affordances.

- Interestingly, GPT4-o has improved in some tasks over Turbo and V but regressed in others:

- Significant Regressions: Counting(v: 60.83%; o: 49.17%; Jigsaw (v: 70.00%, o: 55.33%)

- Why? Hard to know, without understanding the architecture choices made in more recent GPT models, but this could be a result of:

- Distillation, with a focus on preserving reasoning and captioning tasks but less of an emphasis on basic visual perception tasks

- Specialist vision models still do better on most of the specific tasks in the BLINK dataset

Counting in BLINK, and related musings

- LLaVA-v1.6 34B leads with 66.67% vs a human score of 97.70% and a random choice baseline of 25%.

- Weirdly, the authors of Effectiveness assessment of recent large vision-language models (June 2024) find that 3 O/S VLMs (including LLaVA 1.5) outperform GPT-4V on counting tasks - getting ~30% each whilst GPT-V get's 0%

- In DeepMind's GeckoNum (Jun 2024) benchmark paper they observe that (img, text) training datasets do include numbers in the captions, but these are scarce. They argue that learning how to bind the numbers to the appropriate image features requires quite a sophisticated semantic understanding of the image.

- Anthropic provide a “best practices for vision” guide in which they demonstrate that good prompting techniques to decompose a counting task can improve accuracy. (Not the lack of sophisticated prompting in the BLINK evals)

- Directly annotating an image with a question (e.g. a maths question) is likely to render it similar to many images in the pre-training dataset. This can work better than providing the question in text along with an unannotated image.

- So we have a question:

- Are the BLINK team right: must deficiencies in working with perceptual primitives be fixed before VLMs can exhibit human-level performance in perceptual tasks; or

- Can strong reasoning compensate for such deficiencies?

- Probably, the reality is that:

- Perception is the primary bottleneck

- Strong reasoning can partially compensate for perceptual limitations

- The optimal solution likely requires improving both capabilities, with priority on perception

- Various commentators (e.g. HF) have suggested that the ViT architecture itself might require review - and/or the contrastive training objectives used.

Multimodal pre-training of a Vision Encoder: Apple’s AIMv2 (2024)

- Recently, the team at Apple reported a different approach to training a fresh vision encoder have taken a similar but different approach to took this by co-training a ViT and decoder with a recipe designed specifically to enhance the image embeddings.

- https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.14402

- Observation is that ViTs are trained using contrastive loss functions, whereas LLMs use generative pre-training - which is one of the secret sauces.

- Can we use generative training to pre-train the ViT?

- Consists of a ViT + transformer decoder setup - both trained from scratch

- Trained on a mix of 12Bn public & private (img, caption) pairs. Captioning a mix of alt-text and synthetic.

- Data is prepared with examples made from img patch tokens + txt tokens (in that order since this will result in a strong vision encoder)

- Training is done using prefix attention: a random prefix of visual tokens is unmasked, the rest of the visual tokens - plus the text tokens - must be decoded (with subsequent tokens causally masked). The decoder’s loss is only then calculated over non-prefix tokens.

- the entire set-up is trained with a next-token prediction task: MSE loss for vision tokens generated, standard cross-entropy loss for language tokens

- Recall that this recipe is designed to yield a strong vision encoder. So the decoder LM can be jettisoned when constructing a VLM. Indeed this is exactly what they did.

- To test the power of the new ViT in a MM architecture, they create a VLM by connecting it to LLaMA3 via a simple MLP and trained on the LLaVA SFT mixture.

- Comparing their new ViT with comparable contrastively trained, drop-in replacements, they see improvements in all benchmarks explored - but particularly significantly in captioning and VQA benchmarks

- I’d be very interested to see how switching the ViT from a leading O/S VLM for AIMv2 affects BLINK performance.

The next frontier: Multimodal Generation

- Understanding images is great; what about generating non-text data?

- The simplest way is to simply have your LM generate a prompt for an image and create that image with a diffusion model. This is what Gemini and GPT-4o are doing today.

- Image-generation supported by OpenAI (via DALL-E) and Gemini (via Imagen 3)

- The GPT-4o announcement demonstrated that the model could directly generate image outputs (”O” is for “Omni”) but this capability has not yet been released. So how might this be working?

Chameleon - FAIR (2024)

- Chameleon: Mixed-Modal Early-Fusion Foundation Models

- Predecessors:

- CM3: A Causal Masked Multimodal Model of the Internet

- CM3Leon (pronounced “Chameleon”)

- Everything discussed thus far has been “late fusion”. Separate modality encoders are used to encode images and text and then the models learn to align the embeddings.

- Is is possible to train a single encoder to work on both images and text?

- The first challenge comes in tokenizing the images. Up until now, we’ve used the term “image tokens” quite loosely - unlike text tokens (which can be decoded via a codebook back into text) the image tokens are continuous.

- The trick is to use a clever bit of machinary - the VQ-GAN. A simple overview:

- Encode and downsample an image, turning it into a set of latent vectors

- quantize the vectors using a learnable codebook of fixed size

- decode the vectors back into pixel-space

- apply a set of losses which consider different aspects of the reconstruction (including from the discriminator in the GAN setup)

- Now, the idea is to train a (LLaMA2) transformer decoder across mixed streams of input tokens.

- The team build a large pre-training dataset:

- Text only: 3T tokens from the LLaMA2 and CodeLLaMA pre-training datasets

- Text/Image: 1.4B open & licensed captioned images, cropped to 512x512

- Text/Image Interleaved: Following IDEFICS, 400B of interleaved image/text data scraped from the web

- The loss function is not explicitly described, but we can reasonably assume it is based on the CM3 (Causal Masked Multimodal Modeling) objective:

- The key to understanding the CM3 objective is to know that a simple, AR (next-token) loss function is insufficient for training over multimodal data.

- This is because, in order to train the model to learn cross-modal relationships, it’s helpful to be able to have some degree of bidirectional attention.

- For example, if there is an image in the middle of a text block, it’s going to be easier for the model to condition on all of the surrounding text when predicting the image tokens.

- The CM3 objective achieves this by introducing random masks to sub-sequences of the inputs.

- Masked regions are replaced with a special mask token and appended to the end of the sequence.

- We can now decode one token at a time, as usual. When we reach the masked subsequences at the end, the model can apply attention to all previous tokens.

- The Chameleon series is important in demonstrating a training recipe for early fusion VLMs which can generate images as well as consume them.

- The FAIR team note that training at higher parameter counts was tricky and they had to introduce a number of tweaks to the LLaMA2 architecture to stabilise it.

- What they demonstrate is that they beat LLaMA2 on most of the text-only benchmarks (again, this finding!)

- It is competitive with GPT-4V and Gemini Pro on captioning and VQA tasks

Transfusion (MetaAI)

- Previous approaches at MM-output generation:

- The Transfusion approach is to pretrain a transformer on 50% img & 50% txt using a next-token prediction & diffusion denoising objective, respectively.

- we don’t need to quantize the images in this architecture, so they are encoded using a VAE Encoder and then turned into “patches” (i.e. ”tokens”) via a UNET or simple MLP

- when decoding outputs can be handled in two ways, depending on whether they belong to a TXT or IMG region:

- TXT regions are handled with a simple linear layer to yield token probabilities

- IMG regions are processed by a UNET up layer & VAE Decoder, trained via a diffusion objective

- Causal attention for text, bidirectional for images

- This allows every image patch to attend to every other patch within the same image, but only attend to text or patches of other images that appeared previously in the sequence.

- Compared to Chameleon, this approach is more efficient - requiring only 1/3 as many flops to match the FID scores.

- INTERESTINGLY: it also matches Chameleon perplexity on text-2-text tasks at 1/2 the FLOPS…

- At 7B params, the model outperforms DALL-E2 and SDXL on the GenEval benchmark, whilst reaching LLaMA1 performance on text-only tasks

- For text, uses the Llama 2 tokenizer and corpus [Touvron et al., 2023b], containing 2T tokens across a diverse distribution of domains. For images, we use a collection of 380M licensed Shutterstock images and captions.

- Training on quantized image tokens degrades text performance more than diffusion on all three benchmarks.

- No instruction tuning was done so it’ll be interesting to see how well the transfusion recipe works for multimodal tasks

- Fine-tuned the 7B model using a dataset of only 8k publicly available image editing examples, where each example consists of an input image, an edit prompt, and an output image. Enables them to assess how well the model can generalize to image-to-image generation - which is not covered during pretraining.

- Team believes that that Transfusion models can adapt to and generalize across new modality combinations - but evidence for this was limited to small-scale, manual experiments.

Frontier Labs Offerings

- Image fine-tuning supported by:

- OpenAI for 4o, 4o-mini

- Google for Gemini 1.5 Pro and Flash

Frontier Class

| Developer | Model | Availability | Date | MMMU 0-shot CoT | BLINK | DocVQA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X.AI | Grok-2 Beta | Proprietary | 13/08/2024 | 66.1% | 93.6% | |

| Anthropic | Claude 3.5 Sonnet (New) | Proprietary | 22/10/2024 | 70.4% | 56.5% | |

| Gemini 1.5 Pro | Proprietary | 24/09/2024 | 65.9% | 61.0% | 93.1% | |

| OpenAI | GPT4-o1 Preview | Proprietary | 12/09/2024 | 78.2% | ||

| Meta | LLaMA 3.2 Vision (90B) | Proprietary | 30/09/2024 | 60.3% | 90.1% | |

| OpenAI | GPT-4o | Proprietary | 13/05/2024 | 69.1% | 63.2% or 68.0% | 92.8% |

| Alibaba | QWEN-VL2 72B | Open Source | 19/09/2024 | 64.5% | 96.5% | |

| OpenGVLab | InternVL2.5-78B | Open Source | 05/12/2024 | 70.1% | 63.8% | 95.1% |

| Llava Hugging Face team | LLaVA-OneVision-72B | Open Source | 06/08/2024 | 56.8% | 55.4% | 91.3% |

Mini Class

| Developer | Model | Date / Version | MMMU | BLINK | DocVQA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X.AI | Grok-2-mini | Proprietary | 13/08/2024 | 63.2% | 93.2% | |

| Gemini 2.0 Flash (Experimental) | Proprietary | 11/12/2024 | 70.7% | |||

| OpenAI | GPT-4o-mini | Proprietary | 18/07/2024 | 59.4% | 51.9% | |

| OpenGVLab | InternVL2.5-8B | Open Source | 05/12/2024 | 56.0% | 54.8% | 95.1% |

| Microsoft | Phi-3.5-Vision- Instruct (4B) | Open Source | 17/08/2024 | 43.0% | 58.3% | |

| Gemini 1.5 Flash | Proprietary | 23/05/2024 | 56.1% | 45.8% | ||

| OpenAI | GPT-4o1-mini | Proprietary |

Why Does Phi-3.5V do so well on BLINK?

- Technical report doesn’t reveal anything novel in the architecture - it’s an AR set-up

- Nor does it give too many details about the datasets used, except:

- 0.5T pre-training tokens from a mixed dataset

- No vision-component to the loss during PT

- A very large SFT dataset - including a significant component built in-house - of 33B tokens

- A DPO step is explicitly mentioned

Concluding thoughts

- Is MM necessary for AGI?

- Top performers on MMMU are large and reasoning-heavy. 4o1-preview takes the top spot.

- However, given the correct training recipes, text-only performance is enhanced by MM pre-training.

- We see interesting regressions in reasoning-heavy models on BLINK, which suggests that we haven’t “solved” VLMs yet.

- I’d be very curious to see how Hybrid VLM architectures like NVLM perform on BLINK, given the duel-mode access to image features.

- Future of VLMs

- Expect to see a lot more on the true-MM models?

- Expect to see the scale of O/S VLMs increase further?

- Expect to see more innovation in the pre-training (or replacement) of ViTs. I have read comments about re-exploring CNNs - but maybe some other architecture is possible?

- Expect to see larger, heavily augmented datasets for SFT and second-stage PT, with new tasks being represented.

- Expect to see more exploration of alignment post-training also.

Full Transcript

Will Hardman: 0:00 Is multimodal understanding in an AI important on the path towards AGI? It's not entirely clear that it is, but some people argue that it is. So 1 reason that 1 might want to research these things is to see if by integrating the information from different modalities, you obtain another kind of transformational leap in the ability of a system to understand the world and to reason about it. I would say in inverted commas, similarly to the way we do. For open source researchers, like the last few months have really seen the arrival of these huge interleaved datasets, which has kind of really jumped the pretraining dataset size that's available. I'm kind of amazed that the Perceiver example works because it feels to me just like tipping the image into a blender, pressing on, and then somehow when it's finished training, the important features are retained and still there for you.

Nathan Labenz: 0:55 Hello. Happy New Year, and welcome back to the Cognitive Revolution. Today, I'm excited to share an in-depth technical survey covering just about everything you need to know about vision language models, and by extension, how multimodality in AI systems currently tends to work in general. My guest, Will Hardman, is founder of AI advisory firm Verity, and he's produced an exceptionally detailed overview of how VLMs have evolved. From early vision transformers to CLIP's pioneering alignment work to today's state of the art architectures like InternVL and LAMA3V. We'll examine key architectural decisions like the choice and trade offs between cross attention and self attention approaches, techniques for handling high resolution images and documents, and how evaluation frameworks like MMU and BLINK are revealing both the remarkable progress and the remaining limitations in these systems. Along the way, we dig deep into the technical innovations that have driven progress, from Flamingo's Perceiver Resampler, which reduces the number of visual tokens to a fixed dimensionality for efficient cross attention, to InternVL's Dynamic High Resolution strategy that segments images into 4 48 x 4 48 tiles while still maintaining global context. We also explore how different teams have approached instruction tuning from Lava's synthetic data generation to the multistage pre training approach pioneered by the Chinese research team behind QuenVL. Our hope is that this episode gives anyone who isn't already deep in the VLM literature a much better understanding of both how these models work and also how to apply them effectively in the context of application development. Will spent an estimated 40 hours preparing for this episode, and his detailed outline, which is available in the show notes, is probably the most comprehensive reference we've ever shared on this feed. While I have not worked personally with Will outside of the creation of this podcast, the technical depth and attention to detail that he demonstrated in what for him is an extracurricular project was truly outstanding. So if you're looking for AI advisory services and you want someone who truly understands the technology in-depth on its own terms, I would definitely encourage you to check out Will and the team at Veratai. Looking ahead, I would love to do more of these in-depth technical surveys, but I really need partners to make them great. There are so many crucial areas that deserve this kind of treatment and I just don't have time to go as far in-depth as I'd need to to do them on my own. A few topic areas that are of particular interest to me right now include first, recent advances in distributed training. These could democratize access to frontier model development, but also pose fundamental challenges to compute based governance schemes. Next, what should we make of the recent progress from the Chinese AI ecosystem? Are they catching up by training on Western model outputs, or are they developing truly novel capabilities of their own? There's not a strong consensus here, but there's arguably no question more important for US policymakers as we enter 2025. I'm also really interested in biological inspirations for neural network architectures or any comparative analysis of human and artificial neural network characteristics. The episode that we did with AE Studio stands out as 1 of my favorites of 2024, and I would love to have a more comprehensive understanding of what we collectively know about this space. I'm similarly interested in the state of the art when it comes to using language models as judge or otherwise evaluating model performance on tasks where there's no single right answer. This is a problem that we face daily at Weimarc and which seems likely to have important implications for how well reinforcement learning approaches will work and scale in hard to evaluate domains. Finally, for now, would love to catch up on the latest advances in vector databases and rag architectures. I've honestly been somewhat disillusioned with embedding based Rag strategies recently, and I've been recommending Flash Everything as the default relevance filtering strategy for a while now. But I do wonder, what might I be missing? In any case, the success of our previous survey style episodes, including our AI revolution in biology episodes with Emily Schreiber and our data data everywhere, enough for AGI episode with Nick Gannon, suggest that people find these detailed overviews to be a helpful way to catch up on important AI subfields. So if you have or are keen to develop deep expertise in an area that you think our audience would benefit from understanding better, please do reach out. I'm open minded about possible topics and very interested to hear what you might propose. You can contact us as always via our website, cognitiverevolution.ai, or by DMing me on your favorite social network. And of course, I'm more than happy to give you the chance to plug your product or services as part of your appearance on the show. Now I hope you enjoy my conversation with Will Hardman, AI advisor at Verity, about all aspects of vision language models. Will Hardman, AI advisor at Verity and AI scout on all things vision language models. Welcome to the Cognitive Revolution.

Will Hardman: 5:54 Thanks, Nathan. Great to be here.

Nathan Labenz: 5:57 Yeah. I'm excited about this. We've talked about this for a few months now, and you have put a real Herculean labor into a a very deep dive into all of the techniques, datasets, different strategies, variations on making vision language models work. I think this is gonna be a really interesting crash course and overview on all that. And, I think it's something that I know that I want and need, and I think a lot of people will, really benefit from getting the sort of fast forwarded version of all the research you've done. So thanks for, putting all the legwork in upfront to make this happen. And, basically, what I wanna do today is just kinda give you the floor, let you take us through everything that you have found to be important in vision language models. And I'll, you know, certainly, have my questions along the way as we go. But

Will Hardman: 6:49 Yeah. Please.

Nathan Labenz: 6:49 I'm excited for this.

Will Hardman: 6:51 Cool. Yeah. So this would have been obviously a lot easier to compile if the field had stayed still for 5 minutes, and the leaderboards hadn't jiggled around every day. And new papers hadn't come out every week, making me think, we should probably include this. But we're we're kind of at a checkpoint in time, so it's worth saying we're recording on 12/20/2024. We're still not the end of the OpenAI 12 days of Christmas, so something may change tomorrow. Paper may be released tomorrow, so this is kind of a point in time view of vision language models. And I guess it's it's a deep dive if, you know, if you're coming from the perspective of someone who's interested in AI, but not super familiar with vision language models. But if we're talking about vision language models specifically, it's definitely not a deep, deep dive into the research because it's huge. And there's so much going on and some of it's so complicated and so much we could cover. So what I thought we could do is just stick to like a few things. So firstly, let's look at some of the most important architectures and some of the trends in research. We'll illustrate these through some of the most notable models from the last couple of years. And these will be models that anyone who's working or building this space is quite likely to encounter. And then we'll talk a little bit, I mean, touch briefly on the key data sets and some of the benchmarks. And 1 benchmark in particular we'll explore in a bit more depth because it's really interesting. And then I guess we'll talk a bit about recent attempts at what we call true multimodality. So a vision language model is really reading kind of audio sorry, images and text inputs and then reasoning about them. But true multimodality would be generating images as well. And so we'll we'll kind of come onto that at the end. And then kind of we'll finish off, I think, just by taking a kind of as of today snapshot, what's best in class across some of the key benchmarks and where do I go and get it and what can I do with it?

Nathan Labenz: 8:45 That sounds good? Sounds good. Yeah. I'm already taking away that you're not classifying me as a truly multimodal entity in as much as I can't produce image outputs. So the talk about the bar rising quickly. I think I'm already outclassed by what you're calling the true multimodal models.

Will Hardman: 9:04 You mean you can't draw?

Nathan Labenz: 9:06 Not very well. Not not well enough that I would I would not see an API anytime soon. That's for sure.

Will Hardman: 9:11 Yeah. So in that case, I'm like you. I mean, I can just about doodle. That's about it. Because let's just to start off, like, all good research overviews with a motivation section. Like, why do we care? Because, obviously, there's lots of interesting use cases for VLMs. It was really interesting recently when you had the team from Google who were talking about the new Gemini APIs. 1 of the things they said was loads of people are building with large language models. Relatively few are building right now with visual language models. And that's, they think, gonna be a growth area next year. So that's that's kinda cool. There's there's loads of kinda use cases. The obvious ones like medical assistance, you know, being able to look at an image modalities as well as patient history and then say things about a patient that might be useful to the clinician. But I mean other use cases, content filtering, for example, and knowing what is in an image and text, for example, if you were looking on a social media platform and you're trying to screen out images or content of concern, indexing large quantities or archival material or product catalogs or something like that, where you've got both visual components and text components. You want to better understand, you know, what is this product given I can see it and given I've got some information about it. But I've also seen applications, for example, in insurance where people are having photos of cars, for example, there's a description of what's supposed to have happened to the car, there might be some damage, and the question is can I actually see the damage in the image? Does it kind of reflect what the person was saying on the report? Yes or no. There's various use cases. But I think beyond that, there's kind of 2 other reasons we might be interested in visual language models. 1 of them is that in building VLMs, you're learning to do is integrate 2 modalities. They start off very separates and somehow you're gonna reason over both of them. And then if you can find the recipes for doing this right, then into the future, you can think about, okay. Can I integrate audio, touch data, LiDAR data, other modalities? And if you think about, like, for example, robotics of the future, which you think about the number of kind of different sensory modalities you need to have a robot cook a meal, you know, it's got to handle everything, see everything. You can think about VLMs as being the first step to learning how to do this so we can integrate lots more for the future. So that's kind of a longer term thing. Secondly, and it's a bit more of a philosophical question is, is multimodal understanding in an AI important on the path towards AGI? It's not entirely clear that it is, but some people argue that it is. So 1 reason that 1 might want to research these things is to see if by integrating the information from different modalities, you obtain another kind of transformational leap in the ability of a system to understand the world and to reason about it. I would say in inverted commas, similarly to the way we do. We know they don't do things the same way we do. There you go. And I guess there's arguments against, know, is it important would be to say, well, look, frontier language models show lots of evidence of high level abstraction, world models, sophisticated reasoning. There's no obvious ceiling in performance as of today. Maybe a grounded multimodal understanding of the world is not that important for achieving AGI. But we'll kind of explore this. Maybe there are some little bits of evidence we'll come across today which might point us towards 1 or the other view here.

Nathan Labenz: 12:40 Yeah. I mean, I would be very surprised if we end up I mean, it just seems like imagine yourself unable to see. Right? It's like it would certainly be a major hurdle to have to get over. And my guess is that and maybe we'll, you know, shine some, light, so to speak, on this question as we go. But my guess is we'll never really answer that philosophical question of, like, could we have built an AGI that isn't multimodal? Because, you know, to state the most obvious spoiler in the history of the world, like, there has been a lot of progress, and it seems like if nothing else, it will be the path of least resistance. Like, multimodal is clearly going to work. The details are to be unpacked, but it seems like maybe, you know, the sort of philosophical crowd will continue to say, well, we might have been able to do it without multimodality or it would have been impossible. But, you know, it seems like in the end, this is going to be the norm and these things are gonna walk among us. Probably, if I had to guess, you know, sooner rather than later.

Will Hardman: 13:43 There's always sooner rather than later. There's no in this world. So I suppose before we dive into the first vision language model that we'll cover, there's probably 2 important little prefaces we ought to do. 1, we ought to talk about vision transformers for a moment. And then we ought to talk about the CLIP model from OpenAI. And the reason is that both of these are gonna crop up again and again. So let's just kind of refresh our memories as to what they are. And then we'll kind of dive into the VLMs themselves. So the vision transformer itself. So I'm going to assume we're all familiar with a language model transformer, especially decoder architecture. The canonical paper here is called An image is worth 16 by 16 words, which is from Google about 4 years ago now, 2020, I think. And previous to this, like most vision models have been based on convolutional neural networks. So they've basically been stacking convolutional filters to extract more and more global features from the images. And the question that the Google team asked was, Well, could we use the transformer recipe to build something that understands images? So the recipe is, let's say, quite straightforward. You take an image and you divide it into non overlapping patches, like this. Okay? You then linearize the patches and you have a linear embedding, which basically converts them all into tokens. Okay? So now we have just a sequence of visual tokens through a learned embedding. And then we feed these patches 1 x 1 into a transformer encoder, and we use full attention across it. So every little image patch can pay attention to every other image patch in the image. Okay? This is very similar kind of in thinking to to how a model like Bert is trained. Because what we do is they stick a classification token. They propend it to the sequence. And the training objective is, can you classify the image that you've seen into 1 of a large number of categories? You take the classification vector out the end, and that's what you used to figure out if you got the right classification. So very, very simple recipe going on there. And the key finding was that if you make these things big enough, these vision transformers, the transformer architecture does beat the convolutional neural networks of the day. And so that makes it a very kind of useful building block. There's just a couple of things we ought to take away from the design of the vision transformer, which is also called a ViT. So I'll probably use the word ViT throughout. The first is that note the image resolution is going to be fixed by design. So in the original vision transformer, was 2 24 pixels square. Okay. So everything has to be that size when we treat it in. Then we get fixed number of patches coming out. For the original training, they would stick, like I said, this classification token in. But when we come to talk about the vision language models later, normal practice is to take the entire sequence of hidden states from the transformer out and use that as your encoded image. So we don't just take the classification vector, we take everything. And that means you could get quite a lot of vision tokens out of such a model. So if you started with 2 24 times 2 24 is your image size and your patches were 16 times 16, bit of the back of the envelope math sells you, you're gonna get 196 visual tokens out of the end, which can be quite a lot. Okay? So that's the other thing to note. I guess the third thing is, and this is just a convenience, when we talk about vision transformers, you'll hear them describe like ViT H16, for example. And this just tells you something about the kind of dimensionality of the vision transformer. So the ViT is telling us a vision transformer. The h in that stands for huge. We just have to know that huge stands for about 600,000,000 parameters. And the 16 tells us the patch size. So that's what we're patching our images up into. So if I use that later on in here, you'll know what I mean. I say VITG 16, for example. It's a giant 1, which is even bigger than huge. There we go.

Nathan Labenz: 17:49 Hey. We'll continue our interview in a moment after a word from our sponsors. So couple little follow-up notes there just to make sure I understand this correctly. 1, just to contrast the image attention pattern versus the language model attention pattern, at least the 1 that we're most familiar with, which is like a look back only pattern, right, in language, the attention in the image context is generally all to all. Right? So there's no Cool. There's not, like, a sense of ordering or the sort of you know, obviously, language unfolds token by token. So that's 1 kind of fundamental difference. It's just that this is more of a which obviously reflects the modality itself. Right? The image is a snap of a a scene in time, and that is all on par with each other in the way that it's being processed all all to all. The other thing that I wanted to dig in on just a little bit more is how the tokenization happens. In language, we have these tokenizers, which sort of try to figure out, like, what's the sort of optimal way to and it's interesting that those are typically not part of the end to end training. Right? You sort of have this this this separate sort of bolted on system that, you know, people have try have kind of hated and have tried to get rid of for a long time, and maybe there's some signs that that could be about to happen. It's interesting. I was just reading last night a paper from Meta that's about a more dynamic, way to batch text as opposed to with these fixed tokens that are predefined. But

Will Hardman: 19:29 Sure. Yeah.

Nathan Labenz: 19:30 You know, if if anybody hasn't seen this, you can go to the OpenAI tokenizer and just paste in your text, and it will immediately chunk it into bits of text and color code them, and you can see what all the tokens are. So that's a vocabulary of Yep. Think now up to, like, a 100,000 different little bits of text that text is broken down into before it is translated into numeric form and then processed. And that translation of this token to this vector representation is something that at runtime is fixed, and there's basically as many Yep. People often refer to this as 1 hot encoding where there's as many possible input vectors as there are tokens. Yeah. How that that's a bit different now in this case, right, for images. My understanding, if I'm understanding correctly, is there's not, like, a fixed vocabulary size of

Will Hardman: 20:29 That's

Nathan Labenz: 20:29 of possible tokens. Right?

Will Hardman: 20:30 That's correct. So we're gonna use the term throughout most of it. We're gonna use the term tokens quite loosely because as he correctly says, you know, tokens can be mapped back to text through a code book. Literally got, you know, 80,000 codes. You look it up and you get your byte pair or whatever it is at the end. The same is not the case with visual tokens. They exist on a continuum, as you pointed out. So to go from your little patch, which is really just a matrix, you've got some few dimensions and channels in there. You're simply going to pass that through a matrix, which is going to generate you the vector that you want to stick in to the transformer. And it's learnable. That transformation is learnable. But the important thing is that your tokens are going to come out on a continuum. Okay. And they don't need to be quantized at this point. There's nothing in the transformer architecture that says tokens have to be quantized to a code book. You can still run the attention mechanism even if your tokens exist on a continuum like this. Okay. Cool. Note that because we're training, like you said, the visual, the vision transformer with a classification objective, we don't actually have to decode anything at the end. So it doesn't matter.

Nathan Labenz: 21:43 I'll then I'll save my next question I have for as we get a little deeper into the journey here. I think the last thing that's worth just reflecting on for a second is just how small the images are that are being processed. So I've done a little bit of this, not recently because these days we have these foundation models where I can just throw basically anything into it. I think

Will Hardman: 22:03 Yep.

Nathan Labenz: 22:03 There are some hard limits that I've run into occasionally if my image is, like, north of 10 megabytes or whatever. But typically, just throw it in there. They handle it. You as a developer don't really have to worry about it. With earlier generations of models, you did have to do this sort of preprocessing where you would take your image. It was your responsibility as a user of the model that somebody open sourced for your, yeah, convenience to take your image and basically morph it or, you know, I guess resize it is probably the the right term into the required size that the model could handle. And it's, you know, presumably just because everything was smaller back then and, you know, compute resources were more limited and the results weren't so spectacular in general. Mhmm. 2 24 x 2 24 even until fairly recently. And even with, like, the OpenAI kind of small mode, whatever their sort of low res mode is, it is remarkable how much performance can come out of these, like, very small images even when they're dramatically shrunk and they're often, like, significantly distorted because your original image might not have even been a square, but you're just kinda like, whatever. I'm just gonna make it a square. I don't care if things are smooshed. I don't care whatever happens. That's what we're gonna work with. And it's amazing to me how well that actually works. And and I think these days that's getting liberalized for sure because it's not all low res on, like, the OpenAI API, but it is remarkable how far that can go.

Will Hardman: 23:33 Yeah. Without wanting to spoil the big reveal, of course, they're not compressing everything to 2 2 4 x 2 2 4 and using that as the image inputs. There's a much more sophisticated and smarter things going on, at least with the the leading visual language models. So we'll see how they do it in a bit.

Nathan Labenz: 23:51 Okay. Cool. Well, let's carry on. That's a great start.